Wu, Amy (2021) Farms to Incubators. Women Innovators Revolutionizing How Our Food is Grown. Fresno, California: Craven Street Books.

Ellen Messer (Tufts University)

This book, like the documentary film of the same name, features fabulous short case studies of (mostly) minority women entrepreneurs, who use information technology (IT) tools and business design and networking skills to craft precision agricultural approaches to farming and food processing that can reduce waste and pollution in U.S. and world food systems.

Incubators are investment and networking platforms that match innovative entrepreneurs with investors and business mentors who can guide start-ups through the scale-up and marketing process. The stories here concentrate on those businesses that have prospered through the California-based THRIVE forum, which uplifts and mentors predominantly California businesses in the Sacramento (including Salinas) Valley and beyond. But some examples featured in this book reach beyond, to other U.S. regions, Europe, Turkey, South America (Colombia, Brazil), and Australia. For most but not all participants, Stanford University provided the key training ground for IT and innovation. Dozens of examples also originate in state schools and agricultural programs, across the U. California system and other places like Indiana, where state funding for agriculture and education has contributed financing for networking platforms, as well as academic and professional trainings in diverse inter-disciplinary fields like computer science, various kinds of engineering, biology, soil and water sciences, and business. Diversity in all forms (social, technological, crop-related bio-physical developments) is a theme cross-cutting these developments, which feature biographical profiles of these women entrepreneurs, their family backgrounds, education and technological strategies, as well as diversity in cropping strategies and environmental management.

As a set overall, the examples showcase how young educated entrepreneurial women, mostly women of color, create data-driven farming based on information-technology, artificial intelligence, and robotic tools for precision agriculture. They tell and share women innovators’ stories and amplify women’s voices in recounting immigrants’ success in family or start-up farming businesses. These young women of color are modernizing land, water, crop, and ecological management in what had been a white, male-dominated sphere. These traditional male farmers relied on local knowledge, not data platforms supplied by electronic networks and primary information gathered and analyzed by sensors, drones, and other machines programmed with artificial intelligence. The goal of this new modern ag-food tech businesses is to advance and combine agricultural data science, algorithms and artificial intelligence to improve efficiencies of all factors. In the process of innovating, then scaling up, individual cases illustrate how young women who might not have come from farming backgrounds listen and learn the food system by shadowing farmers and crops from field to market, and learn to appreciate the complexities of agricultural production and food-processing and also commercial and investment environments.

Some of the cases that particularly caught my interest were stories of businesses focused on soil analysis and product quality evaluation, including food-safety. These functions have all been thoroughly transformed by sensors, AI algorithms that read, analyze, and display data, and communications platforms that direct the findings efficiently to those who need it for decision making. One outstanding example is Miku Jha’s company AgShift, that has developed an AI enabled platform that reduces the high-value produce (berries, nuts) inspection process from a human eight to ten minutes to an automated twenty seconds! The material technology includes the multi-faceted inspection machine (named Hydra) along with the package of information on every aspect of quality that has been formulated into algorithms using neural network technologies to automate the grading (pp.38-39). Poornima Parameswaran and Diane Wu’s business Trace Genomics, based in Burlingame, CA, crafted a soil-testing kit for growers that integrates biology (DNA sequencing of microbes), agronomy, data science, and software engineering (machine learning) to detect disease (pathogen types and levels) and soil-fertility deficits, that allows farmers to optimize soil treatments for particular crops (pp.20-21). Additional stories describe pasture range management that hugely improved productivity and revenues. Because year by year I have followed the history of the Greater Boston-based firm IndigoAg, which analyzes soil microbiomes and manufactures associated seed-dips to improve crop performance, I found the story of INARI’s CEO (Ponsi Trivisvavet) of special interest. She helped advance the Asian seed businesses first, of Syngenta (a leading seed-chemical conglomerate), then IndigoAg, and finally, start-up seed company INARI, which gene-edits row crops to precisely fit into their carefully mapped environmental niche analysis.

These are stories that combine not only agricultural understandings, but also IT, AI, and business skills and acumen, and investor-management and marketing savvy. The colorfully illustrated volume overall describes these entrepreneurial profiles and trajectories, in the context of the additional infrastructure that spurs success. In the California cases, this infrastructure includes the university innovation and design hub at Stanford and state institutions, and West Coast government and private investment in training, mentoring, and networking events where young aspiring ag-tech entrepreneurs can gain insights and assistance from farmers, marketers, and business experts. These have been hugely significant in accelerating business ideas, plans, science and technology, and ag-tech progress. The female networking, arguably, has also been significant to accelerating progress among women leaders.

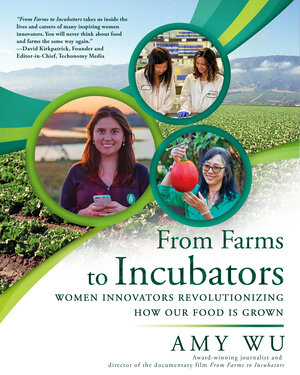

For teaching purposes, this volume is straightforward, easy to read, helpfully illustrated with family, farm, greenhouse, and laboratory photos. The initial case studies, two to four pages long, trace California business paths, not all of which are straight and in certain cases involve reverses due to changing conditions, family issues, and competition that is growing across the ag-tech world.

The final series of case presentations are even shorter, with capsule reviews of additional innovative ag-tech businesses; for example, Phytoption LLC, a “food is medicine” natural ingredients business co-founded by CEO Joanne Zhang in West Lafayette, IL (sic; should be Indiana) (pp.172-174). After these inspiring examples, there is a summary conclusion by story-teller Amy Wu and Food Tank leader Danielle Nierenberg, who gratefully applauds these efforts by young women entrepreneurs to fix particular pieces of broken food systems.

Each story is illustrated with colorful photos of the women entrepreneurs in business-networking and marketing situations, laboratories, agricultural fields and greenhouses, and also family photos. For a “Culture and Agriculture” professional, a provocative question to ask is: what are the old and new roles of human insight, learning, and culture in this burgeoning ag-tech innovators’ world? A key point of the data-driven scientific farming examples is that AI learning, including the tools of artificial neural networks, outperform human “eyeball” and cultural experience in identifying soil and crop conditions and crop safety and quality. There is an emphasis in ag-tech business on being “disruptors.” But there are also continuities and human inputs into the design of each component of these systems. How might the human factors be most productively analyzed? Along these lines, business schools teach entrepreneurs and investors to identify “scalability” in technologies, a term that comes up over and over again in the decision-making of these entrepreneurs. What are salient dimensions and how is scalability related to agricultural culture, continuation or rejection of traditional niche crops or varieties? What are the characteristics of incubators that more or less successfully connect and network women entrepreneurs in agrifood tech? How are spatial, time, and personal (social) frameworks salient? How do these women use terms like “food system,” “food security,” and “sustainability” in their conceptualizations and/or marketing? Or a policy exercise comparing advantages and disadvantages of adopting “Red Melon” as a source of (precursor) vitamin A (Vietnam) or GMO Golden Rice? The film is also a great way to raise and structure discussions about gender issues in dedicated or general courses.

One can read more, follow the cases, and explore what happened in this fast-paced and ever-changing ag-food tech scene. (For example, a quick check of INARI’s website indicated other female principals in the leadership team also held high positions in Big Ag seed companies (Bayer/Monsanto).) Thus, the brief case studies presented here contains the seeds of follow-up projects that can help students explore ag-food tech and female entrepreneurial developments over time.

Classes can also access the documentary at: https://www.farmstoincubators.com , which has all the key words that ground and connect these studies.

I plan to use the book and the film in a course on U.S. Food Policy and Cultural Politics, across two modules that focus respectively on ag-food innovation and food safety. As additional inspiration, and for focus on community-building in addition to technology tools, I might also feature Danielle Nierenberg’s thought provoking “Afterword,” “The Road Ahead” in the introductory readings to one of the three sections in this course: policy overviews, special topics, and community-based food security, which includes the topic of waste reduction across the food system, which is a prominent theme throughout these examples. (I accessed the 27 min. documentary film here: https://www.womensvoicesnow.org/films/from-farms-to-incubators )

This book would also add value dimensions to courses on cultural diversity and on Asian Americans or other immigrant groups, and to multi-generational studies of those who stayed on farms while many or most moved to non-rural locations for other opportunities.