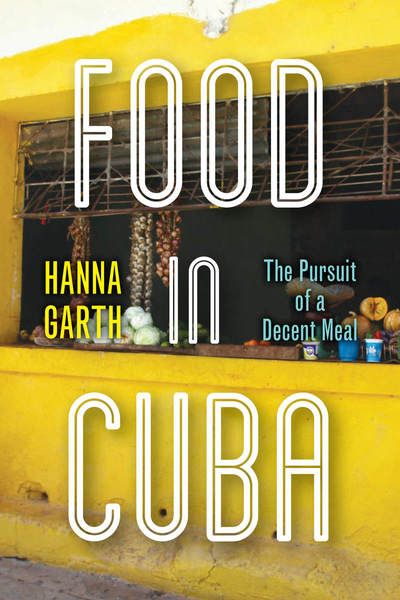

Hanna Garth. Food In Cuba: The Pursuit of a Decent Meal. Redwood City, CA: Stanford University Press, 2020. 232 pp. ISBN 9781503604629

Emily Yates-Doerr (Oregon State University/University of Amsterdam)

My plan was to review “Food in Cuba” from Havana. The Society for Medical Anthropology’s meetings were scheduled to be held there this March. I had dreams of sitting on a patio overlooking the Straits of Florida, book and pencil in hand, a spread of elote hallacas to tide me over while I worked. Hanna Garth writes about how Cubans refuse to lower their food standards, ever in “pursuit of a decent meal” as a part of their commitment to living a decent life. I wanted to observe this firsthand in some small way as I reviewed the book.

Then COVID-19 began to circulate globally.

In the United States, I heard news of public health failures. Workers without federally protected sick leave who had tested positive continued to show up at work, not wanting to risk losing their income or jobs. The food magazine Eater notes that “restaurants and delivery services are notoriously hostile to shift workers calling in sick,” creating ideal conditions for the virus to replicate.

Just before my flight departed I decided not to go. Conference organizers had not canceled the conference. Their email in the days leading up to the conference relayed a message of calm, “It is also reassuring to know that Cuba has a very strong epidemiological surveillance system built on a well-articulated primary health care system.” Friends already in Havana relayed the message that life in Cuba, where daily routines already contained a good deal of “existential uncertainty” (p. 18) seemed to be continuing on without heightened fear.

This was not the case where I was in the United States. A radiologist at a local US hospital told me of seeing scans of lungs full of fluid, while a nurse spoke of waiting rooms of patients with fevers and dry coughs. These patients were not being tested because there were not enough tests. Meanwhile, in nearby counties where children had tested positive for coronavirus, administrators had to keep schools open because children who lived deeply in poverty would go hungry without school lunches.

When I decided not to travel to Cuba, there were no reported cases of coronavirus where I live. What was being credibly reported was that years of gutting public infrastructures – health and otherwise – would soon be catching up with us.

In retrospect, it’s perhaps fitting that I acted out an epidemiological logic — practicing social distancing to discourage viral spread by not traveling — while reading and writing about Cuba, a country known for encouraging “self-sacrifice for the good of the collective” (p. 114). Garth’s book explores the daily life struggles and successes to lead a decent life in a place with one of the most effective community health programs in the world, but where there is also widespread “culinary discontent” (p. 160).

Food in Cuba is based on intensive ethnographic research with 22 families in Santiago de Cuba in 2010-2011 and follow-ups in the years since. As a method, Garth participated in what she calls “ingestive practices” (p. 23) of household food acquisition activities, spending roughly a month deeply immersed in each family’s activities. She complemented this deep engagement with interviews and life histories of more than 100 individuals who worked to find food in this small, powerful island country that lies in the heart of the global project of modernity.

One of the book’s most powerful contributions is to explode the myth that people in conditions of scarcity will eat whatever they can simply by virtue of their precarity. Instead, the participants of Garth’s study care deeply about the taste, quality, and provenance of their food. They spend tremendous energy provisioning ingredients that reflect their cultural and national identities and they maintain an “intensely emotional” connection to their meals (p. 46, 53). While the Cuban government celebrates that there is “no hunger in Cuba,” Garth shows how people will feel stressed, anxious, unsatisfied, and even traumatized when they cannot find appropriate food. Rice, for example, is both scarce and a necessary component of a ‘real’ meal. Without it, satisfaction is impossible.

Each chapter explores an aspect of the ‘politics of adequacy,’ a phrase Garth develops in reference to how Cubans prioritize relational aspects of eating alongside any evaluation of whether food quantities are “enough.” As she explains, “the framework of adequacy can account for what is necessary beyond basic nutrition, prompting us to ask not whether a food system sustains life, but whether it sustains a particular kind of living” (p. 5). Throughout the book’s five chapters she connects the politics of adequacy to a broader political lucha (struggle) to maintain a good life through arts of invention.

Driven by a feminist commitment to the analysis of power relations, the book unpacks how race, gender, sexuality, and class politics all effect the production and consumption of daily meals. Garth, with the skill of an expert chef, pays close attention to the quiet and unspoken details of food procurement to show how Cuban nationalism has always been tied to Cuban cuisine, with women shouldering the burdens of Euro-American colonialism and socialist revolution alike (p. 67). She offers a history of Cuba through stories of food access, where flavorful ajiaco stews mark sites of contested patriotism, and small cups of sugared coffee are filled with the paradoxes of sweetness and calamity (“We never have food, but we always have sugar, always” one informant tells her).

The text is full of thick descriptions of how people make meaning in times of political unrest and global extraction. Alongside stories of anxious scarcity and unevenly experienced fears of breakdown are stories of shave ice in the summer, or the whistles of pressure cookers on narrow-cobblestone alleys while the scents of garlic and onion waft through the air. One especially poignant vignette, set amid the slight intoxication of drinking cheap state-subsidized beer while people dance in the streets, describes the sadness and anger of a man sobbing at the reggaetón lyrics “Give me… a little bit of anything so I can feel happy. It could be a soda or a tube of roasted peanuts.” Life’s small mundane details, Garth shows us, are anything but insignificant.

Garth undertakes a careful critique of how ideals of “community” transforms in the shadows of global capitalism and international sanctions, showing how Santiago de Cuba remains stratified through the nexus of skin color, class, and culture, with often discriminatory effects on darker-skinned and LGBTQ+ Cubans. Promises of gender and racial equality may have launched Fidel Castro’s socialist platform into power, but she demonstrates that patriarchy remains a reigning force in the culinary lives of Cubans today (p. 163). Ethics of socialismo (socialism) frequently give way to practices of sociolismo, where people use personal networks to access private, illicit goods for their immediate family or themselves. One informant shares stories of putting locks on the cabinets of her own home as “community borrowing” morphed into outright theft (p. 132).

Food in Cuba is an excellent text for food studies classes at all levels (I plan to assign it in both undergraduate and graduate ‘anthropology of food’ courses). Garth offers a literary masterclass in how the analysis of food can help us understand social relations while the analysis of social relations can help us understand food. Foodies will appreciate the colorful descriptions of how quimbombó, boniato, plátanos, malanga, or chicharrones give rise to the “flows of daily life” (p. 167). In the process of reading about the cuisine they will learn broad political lessons about how people are luchando la vida (struggling to survive) in Cuba’s declining welfare society, where the influence of global capital looms large and state supports are disappearing.

A good deal of hope, resilience, and solidarity fills the pages of this slim and accessible book, but the final image offers an ominous warning about this moment of global fragility in which we are living: after hours of scouring for ingredients, Garth’s longtime Cuban friends managed to procure a delicious meal. The table in the photograph shows beefsteak, hand peeled potato-fries, cucumber-avocado salad, and those hallacas I’d been imagining when planning my trip to Cuba. It would be a joyous image except for one thing: the table is set for one. In a time when social solidarity is needed to get through crises, be they pandemic viruses or food scarcity, the image of the solitary place-setting speaks to me of the struggle for a decent meal yet to come.