Andrew Mitchel

PhD Candidate, Department of Anthropology

The Ohio State University

On March 25th, the Society for Applied Anthropology Annual Meeting in Portland, Oregon hosted a Traditional Foods Forum with presentations and sessions from indigenous elders, community actors, and academics from across Oregon and Washington State. Each presenter called our attention to critical aspects of the relationship between people, place, climate, and food; the critical knowledges held by indigenous communities; and need to preserve the natural world and its resources in the Pacific Northwest and across the globe.

Eric Quaempts is the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation Director of Natural Resources from northeast Oregon. His keynote presentation focused on reciprocity and first foods of his community. He described the connections through cosmology embedded in how foods are served in ceremonial contexts. He also discussed how modern processes have disrupted the cyclical distribution of energy and resources. One example Quaempts gave was how dams block the movement of salmon from their birthing streams, down to the sea and back to their birthplaces to spawn, die, and provide these nutrients. He also discussed how natural wildfires can be ‘good’ and provide a means by which to reset local ecologies by clearing land for differing biomes and plant spaces like huckleberries and camas root. These dynamics showcase that indigenous communities center their own lifeways and also know how processes of modernity that appear to be positive (hydroelectric power and an overemphasis on fire prevention) have negative impacts on their foodways.

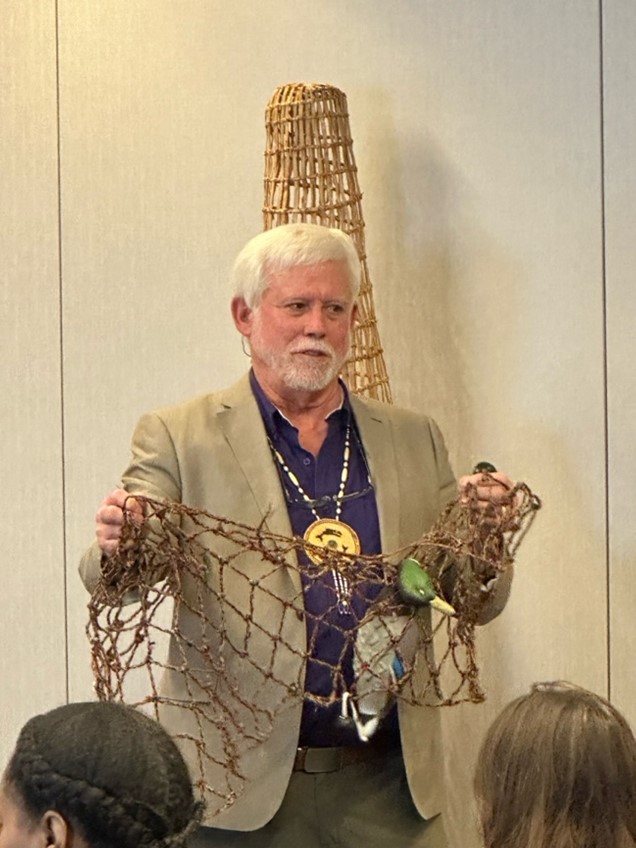

The next session was a fascinating archeological examination of the various basket weaving traditions present in the Salish Sea around Washington State. Suquamish elder Ed Carriere and Dr. Dale Croes from Washington State University did what was in essence a show-and-tell of Ed’s various baskets used in local hunting, gathering, fishing, and other activities. Ed described how his community made use of various parts of local plants, especially cedar, to weave these baskets. He also created various ‘archeology baskets’ that combined his own knowledge but also the various ancient technologies and methods of weaving from across history of the local communities. He also brought with him his own life story basket, which you see in the image below on the left, and other weaved products for fishing like salmon traps and duck nets, which Dr. Croes is holding up on the right. These amazing weavings showcase the nexus of culture, science and art, but also capture the critical technologies devised by indigenous peoples as a practical means of catching, holding, and even cooking local food products like salmon, duck, and berries.

Wilson Wewa from the Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs Tribal Council in central Oregon discussed in his keynote the importance of utilizing and preserving the resources of the land. He described his own efforts at going out to dig for roots during the season where they are sprouting, and the ground is soft enough to dig. This is a practice he learned from his own grandmother, and had typically been women’s work, yet something he himself enjoys and has passed along to his nieces. He said they continue to pursue indigenous medicinal practices over Western solutions like cough syrup. Wewa was critical of the perspectives of local academic communities and those who do not take indigenous perspectives around botany and other practices into account, a critical demand of his in places where elders like himself have deep knowledge of the land and what grows on it.

Elaine Harvey and her collaborators showed a film at the conference entitled These Sacred Hills about the demands and efforts by the Rock Creek Band of the Yakama Nation in eastern Washington focused on protecting critical ancestral lands from development. What is fascinating about this development, the Goldendale Pumped Storage Project, is that it is a green energy project promising to provide sustainable, community-focused energy. However, as it would move water from one holding pool to another through an underground pipe to produce and store energy, if completed the project would dig a hole through a critical sacred site, the Pushpum mountain, for these local indigenous communities. Throughout the documentary and in the intervening question and answer period, it became clear that these sacred sites are seen as empty spaces for development across eastern Washington and there is a complete disregard in these plans for the sacred nature of these sites. These green energy projects also disrupt indigenous foodways with outside efforts to put solar panels and wind turbines coming with consultation for spaces where roots and other edible foods critical to indigenous life grow. Elaine and her collaborators pointed out they must be selective about which projects they fight, as these outside development groups are proposing dozens in the area, and they do not have the resources to properly respond to them all. These processes, which the documentary highlights as neocolonial, show the devaluation of lands where indigenous people still live and use to find food, and that green energy, in the view of these communities, is just neoliberal economic development under a different name.

The final keynote of the day was by Warren KingGeorge, a historian from the Muckleshoot Indian Tribe in Washington State on the traditional value of endemic resources for his community. He focused on archival representations of his community available in repositories like the University of Washington’s special collections that depict the persistence of practices like smoking salmon in longhouses using open fires. KingGeorge reiterated the core importance of continuing these practices and understanding where they come from in the past lifeways of their ancestors. He had many photos of his own family, including his father, to showcase this is not just a conversation about a nameless past, but a critical way to pass along ways of life that no one in his community wants to lose.

These presentations and conversations showcase the critical ties between the food system of indigenous communities and broader discussions around land use practices and misalignments, stewardship of the land, the cultural productions captured by food processing and production, and historical remembrances of local ways of eating. This forum was a fantastic space where all assembled learned a great deal about local practices and engaged in thoughtful consideration of the knowledge and issues faced by these communities seen in the loss of traditional knowledge, the devaluation of their practices, and attacks on their land and culture from outside interests. Ultimately, understanding and preserving the food systems of indigenous communities not only enriches food studies but also encourages a profound respect for diverse cultural practices and the urgent need to advocate for the rights and sovereignty of these communities in the face of various modern challenges.