Samira Bechara

University of New Orleans

I am a budding historian researching wine in Lebanon, particularly French policy and Lebanese wine legislation during French colonization under the League of Nations mandate. The cultural nature of my area of research requires an interdisciplinary approach, for which I’m working on a survey of anthropological literature around wine. When talking about my work, the overwhelming initial feedback is surprise – few are aware of Lebanon’s significant place in the history (and present!) of winemaking. Generally, rather, ideas around wine draw up associations with Frenchness and French culture, thanks to one-hundred-plus years of excellent marketing and legislation by French interests.[i] Wine is inherently a cultural product and in Lebanon it carries deep historical significance to the people who produce it.

Contemplating wine’s genesis leads the seeker to the Middle East. Wine traces its roots to the region of modern-day Iran or Georgia. The neighboring ancient Phoenician civilization distributed it around the Mediterranean in amphorae where it eventually found its way to the Romans. Work has been done in recent years to develop a more nuanced understanding of the role the ancient Phoenicians, who resided primarily on the coast of modern-day Lebanon, played in not only the distribution but also the production of wine.[ii] Beginning in the early 20th century French-educated Christian Lebanese intellectuals, influenced by the likes of Ernest Renan and others, developed a political and cultural theory of Phoenicianism which developed into a national movement before and into the French colonial era.[iii] The Francophone Phoenicianists of Beirut saw the value of wine to their national movement. While discussing the future viability of an independent Lebanese state through the lens of economic development, Naccache writes, “First…the rebuilding of our vineyards, destroyed by disease.” (Naccache 1919) Modern-day Lebanese involved in the wine industry continue to promulgate the Lebanese-identity-as-Phoenician myth to promote a historical legacy of winemaking that pre-dates French colonialism.[iv] The idea of this historical legacy leads us into a discussion of terroir.

Much of wine’s universal value has been gained as a result of the concept of terroir.[v] Terroir is both a reason for and a symptom of the structure of the modern wine industry in our globalized world. In a grounded, practical sense, terroir adds to the value of wine through an assumption of authenticity and distinction. In an idealized, romanticized sense, terroir denotes a quality of soul in a wine, anchoring it not only in a particular place (and with the use of vintages, time)[vi] but also to the people who made the wine. Both ways of conceptualizing terroir can be observed in and applied to developing wine industries and both are necessary to gain a comprehensive understanding of the ways in which terroir adds value to the product. In the case of contemporary winemakers in Lebanon, an embrace of the cultivation and production of wine from indigenous varieties expresses both ways of conceptualizing terroir in a developing industry.

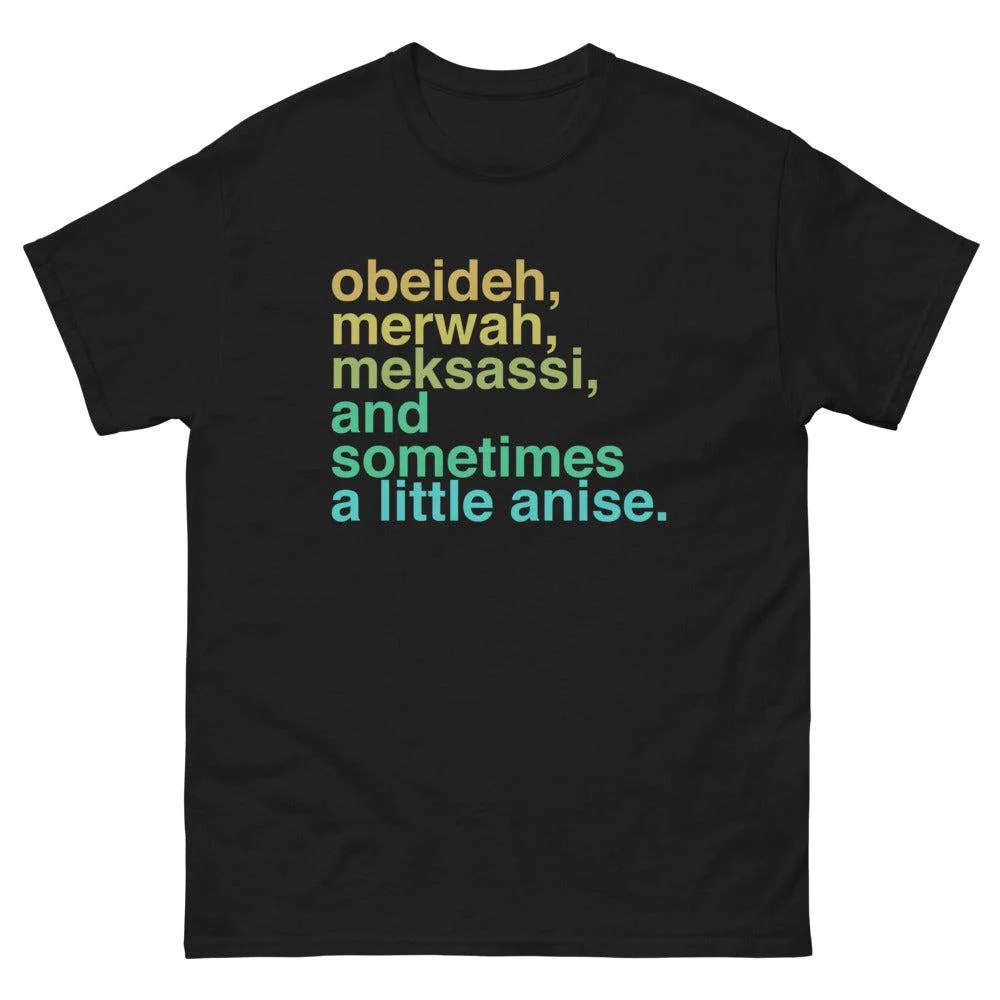

The identification of Lebanese winemakers as the descendants of the ancient wine -making and -distributing Phoenicians offers a sense of historical continuity to their terroir, which is applied through the cultivation of varieties indigenous to the land. The soul of terroir is derived from a sense of historical continuity; in Beaujolais, if Gamay has been the primary variety cultivated since the 17th century, then the terroir of Beaujolais is enhanced by the continued connection of the winemakers to the land. In Lebanon, during and following French colonization, many vineyards were replanted with French varieties. Today, there is a concerted effort by contemporary winemakers in Lebanon to reach back into history and produce wine with indigenous varieties. Taking it a step further, Lebanese winemakers and researchers are working on studies to verify their origins as truly Lebanese.[vii] Confirming the provenance of these grapes would add to the heritage and authenticity of the wine made with them, thus enhancing the soul of their terroir. These efforts are a decade running, and in this time, significant strides have been made in building an international reputation for wine.

The distinction of terroir provides a readily applicable formula to augment the cultural and economic value of a country’s wine. As a result of the value created by terroir in the modern industries of wine and artisanal agricultural products, Paxson has defined a process of the “reverse engineering of terroir” (2010). This process involves the producer of an agricultural product applying the formulas from which the concept of terroir was derived to their own production, seeking to enhance the value of their product. Paxson relates this to cheesemakers in the United States, but it can also be applied to wine producers seeking to make a name for themselves in the global market.

There are clear depictions of the reverse engineering of terroir in various developing winemaking regions. When writing of Chile, Cisterna outlines the plight winemakers have undertaken to reorient Chile’s position in the global market from a producer of value wines to one of fine wines. A facet of their campaign is to promote Chile as a winemaking country that expresses regional diversity based on terroir with an array of grape varieties represented (Cisterna 2013). This process requires the replanting of vineyards from mass-produced varieties to those which exhibit qualities particularly well-suited to microclimates within the country itself. Kopcynska writes about a similar process in Poland, where wine regions are becoming increasingly more selective with the varieties planted (2013). This is both a product of environmental conditions as well as a conscious decision to specialize their wine industry through the creation of terroir. Both the Chilean and Polish winemakers exhibit examples of using terroir as a way to individuate and add value to their product in the global market.

The Lebanese are likewise participating in a brand of reverse engineering of their own by identifying and engaging with their historical lineage in their assertions of terroir. The reclamation of winemaking heritage through the replanting of indigenous varieties in Lebanon ties back to a pre-colonial legacy and enhances the soul of the Lebanese terroir. This serves both functions, the practical as well as the romantic. The practical function is expressed by creating specificity thus exerting the uniqueness of Lebanese wines in the global market. The romantic function is shown by asserting the historical legacy of the Lebanese wine industry, which attributes authenticity to the product. Both these functions of terroir add social and cultural value to Lebanese wine, which, in a globalized capitalist market, is translatable to economic value. Certainly, in this period of economic crisis in Lebanon, a turn of production toward indigenous varieties and the roots of Lebanese winemaking is a forward-thinking tactic to both preserve the tradition of Lebanese winemaking and contribute to the assured continuance of the industry into the future.

References Cited

Black, Rachel, and Robert C. Ulin, eds. 2013. Wine and Culture: Vineyard to Glass. London: Bloomsbury.

Cisterna, Nicolas Sternsdorff. 2013. “Space and Terroir in the Chilean Wine Industry.” In Wine and Culture: Vineyard to Glass, edited by Rachel Black and Robert C. Ulin. London: Bloomsbury.

Daynes, Sarah. 2013. “The Social Life of Terroir among Bordeaux Winemakers.” In Wine and Culture: Vineyard to Glass, edited by Rachel Black and Robert C. Ulin. London: Bloomsbury.

Kopczynska, Ewa. 2013. “Wine Histories, Wine Memories, and Local Identities in Western Poland.” In Wine and Culture: Vineyard to Glass, edited by Rachel Black and Robert C. Ulin. London: Bloomsbury.

McGovern, Patrick E. 2003. Ancient Wine: The Search for the Origins of Viniculture. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Naccache, Albert. 1919. “Notre Avenir Economique.” Edited by Charles Corm. La Revue Phénicienne, July, 2–8. Translation my own.

Orsingher, Adriano, Silvia Amicone, Jens Kamlah, Hélène Sader, and Christoph Berthold. 2020. “Phoenician Lime for Phoenician Wine: Iron Age Plaster from a Wine Press at Tell El-Burak, Lebanon.” Antiquity 94 (377): 1224–44.

Paxson, Heather. 2010. “Locating Value in Artisan Cheese: Reverse Engineering Terroir for New-World Landscapes.” American Anthropologist 112 (3): 444–57.

[i]. The French launched their AOC system for standardizing and regulating wine nearly a century ago. This system has had far-reaching implications and has shaped the minds of those who think about, make, and sell wine worldwide. It developed in two ways: on one hand, trademarking regions reduced the possibility of fraud, and on the other, it led to increasing the value of the product. For a sociological critique on how value is constructed and terroir is used by elites in France, see: Fourcade, Marion. 2012. “The Vile and the Noble: On the Relation between Natural and Social Classifications in the French Wine World.” The Sociological Quarterly 53 (4): 524–45. For a delightful treatise on the process of associating wine (particularly Champagne) with Frenchness and national identity, see: Guy, Kolleen M. 2003. When Champagne Became French: Wine and the Making of a National Identity. The Johns Hopkins University Studies in Historical and Political Science, 121st ser., 1. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

[ii]. From the work of Patrick McGovern in the discussion of wine’s earliest origins to the discovery of a Phoenician wine press at Tell el-Burak on Lebanon’s coast, the narrative is shifting from a depiction of the Phoenicians as having been solely distributors of wine to including its production as well.

[iii]. In the vast literature on Phoenicianism, Kaufman’s piece provides a succinct and approachable history of the ideology, its main proponents, and its link to French culture and Lebanese nationalism: Kaufman, Asher. 2001. “Phoenicianism: The Formation of an Identity in Lebanon in 1920.” Middle Eastern Studies 37 (1): 173–94.

[iv]. Michael Karam, the best-known chronicler of Lebanese wine and its history, refers to this Phoenician connection and in turn gives credence to this idea of unbroken heritage in this podcast: Ronnie Chatah, Episode 363: Wine as a Vehicle with Michael Karam, The Beirut Banyan, podcast video, June 5, 2023, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gcNOVWJ830k.

[v]. In lieu of me attempting to define the concept, see an invaluable anthropological analysis: Demossier, Marion. 2011. “Beyond ‘Terroir:’ Territorial Construction, Hegemonic Discourses, and French Wine Culture.” The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 17 (4): 685– 705.

[vi]. A poignant articulation from Sarah Daynes: “A bottle of wine, therefore, is not just an expression of a place: it is thought to be the expression of a place in time. Like an object of art, a wine is thought to be unique and impossible to reproduce.” (Daynes 2013).

[vii]. Farrah Berrou, a podcaster and independent historian of Lebanese wine, writes about the efforts winemakers and researchers are making to catalog and verify indigenous varieties in this self-published piece: https://aanab.news/p/which-lebanese-grapes-are-truly-indigenous