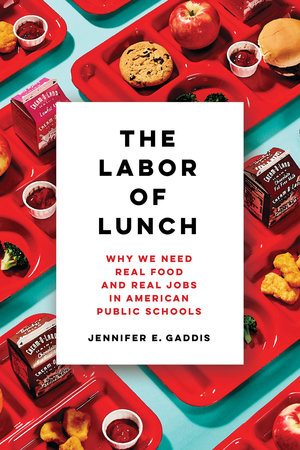

Gaddis, Jennifer E. (2019). The Labor of Lunch: Why We Need Real Food and Real Jobs in American Public Schools. Oakland, CA: University of California Press. ISBN # 978-0-520-3003-3: 291 pages.

Kimberly Johnson (Westchester University of Pennsylvania)

Although school food has been under intense scrutiny for a decade or more, studies of school food labor are limited—until The Labor of Lunch. Author Jennifer Gaddis, provides a fresh perspective on school lunch with a restored history of grassroots engagement leading up to the National School Lunch Program (NSLP) and critique that shifts the dialogue to labor justice. Informed by her own experience with school food and understanding of the NSLP as a powerful lever for change in local food systems, Gaddis began by examining food distribution channels. Her focus shifted as she interviewed lunch laborers across school districts and realized that the labor of lunch was a narrative that needed to be heard.

Gaddis’ transdisciplinary approach to the study of the labor of lunch engages feminist theories in the sociology of care work, critical food studies with its interrogation of race, class, and gender, and environmental sociology. She illuminates the daily context of poorly paid yet essential work of predominantly female and minority school foodservice employees, the role of school food “provisioning as a form of public care”, and the devaluing of school foodservice labor over time as a gendered process. Gaddis brings in a large volume of data to fill in gaps about the socio-cultural history of the NSLP using an extended case study that draws from her observations, interviews, and archival research, for a deeper, intentional understanding across time and space.

The first chapters introduce how changing school food is closely tied to discussions of labor infrastructure, with detailed accounts of past and recent school lunch programs. Here Gaddis establishes the vital role of the predominantly female school lunch employees (“lunch ladies”) in advocating for children, school food, and their own role as laborers. Contemporary calls for universal free lunches, school children participating in the “labor of lunch”, school gardens, and community engagement may sound new. However, Gaddis reveals these were all part of the historic and radical vision of people like Emma Smedley and a host of progressive activists spanning the period from 1890 to 1940 and beyond.

School lunch and cafeterias were not always part of the school day. Advocates fought for school food and better nutrition for children, and as anti-poverty measures to assist working class families. Although we typically start the story of the NSLP with the legislative act named after a male congressman (the Richard B. Russel Nation School Lunch Act), Gaddis details how women school food laborers fought for 50 years to attain this institution. The author exposes how the labor of lunch was not always paid work, but rather part of free labor provided by females. In following chapters, Gaddis highlights waves of political struggle over financing school lunches and distribution of federal funding: the fight for NSLP as social justice to feed hungry children in the 1960s and 70s; the privatization of school lunch distribution channels that de-skilled cafeteria work, reduced jobs to part time while cheapening meals with highly processed foods; coopting of school lunch by Big Food through, “real food lite” that poorly meets new regulations for healthier food while prioritizing cheap food and labor; and contemporary grassroots organizing of school laborers in groups like UNITE HERE for “real food and real jobs”.

In the final summary, Gaddis constructively focuses on change to create fairer, healthier school food systems, sharing evidence of successful school lunch programs across the country. Gaddis concludes with asserting the need to invest in universal free lunch, getting youth, employees, and the community involved, and embedding school food in a “real food economy”.

In The Labor of Lunch, Gaddis restores a grassroots history for a nuanced and complicated understanding of school food and the NSLP, and successfully shifts the frame of critique. The author scrutinizes widespread cultural norms in lunch shaming of children in school, and public shaming of school food workers by the media and celebrities. Her work raises an important critique of the deficit model in our collective response to school food inadequacies. Finding deficits in the individual children and families who cannot pay for healthy lunches without understanding the origins of the problem in low access to resources misses the mark. Similarly, targeting school foodservice workers as uncaring and uneducated about nutrition, rather than interrogating the system that poorly funds laborers and school lunch also engages a problematic deficit model. Gaddis’ work shifts the frame to a justice model and inadequate distribution of resources and funding in the system as the most effective focus for reform.

The author also shifts cultural norms surrounding how change occurs in school food. The culture of shaming and bullying of vulnerable children and poorly paid food laborers traditionally privileges a few celebrities and elite experts with answers for healthier school food systems. Gaddis’ history reveals that large scale change for healthier and fairer school food was grounded in the work and advocacy of poorly paid, poorly acknowledged, predominantly female and minority school laborers. This critique of the critics, shifts the frame of change away from an exclusionary, top-down process. While local efforts demonstrate that change can occur across scale, the common denominator, Gaddis asserts, is the inclusion of school lunch laborers in that change.

Gaddis exposes how civic engagement drove school lunch policy in this well-tooled and carefully researched history. Her work demonstrates how democratic grassroots efforts addressed issues of poverty, disparities, and economic citizenship. This work resonates in our current pandemic era, where food systems are challenged, hunger more pervasive, and essential food laborers in a precarious place. Gaddis offers meaningful engagement with a justice frame that shifts analysis from individuals to the system, and clear evidence that inclusion of school food laborers is essential to sustainable change in school food and a stronger food system.

(See Gaddis’ website helpful information, interviews with school food workers, and ideas for educators: http://www.jenniferelainegaddis.com/)