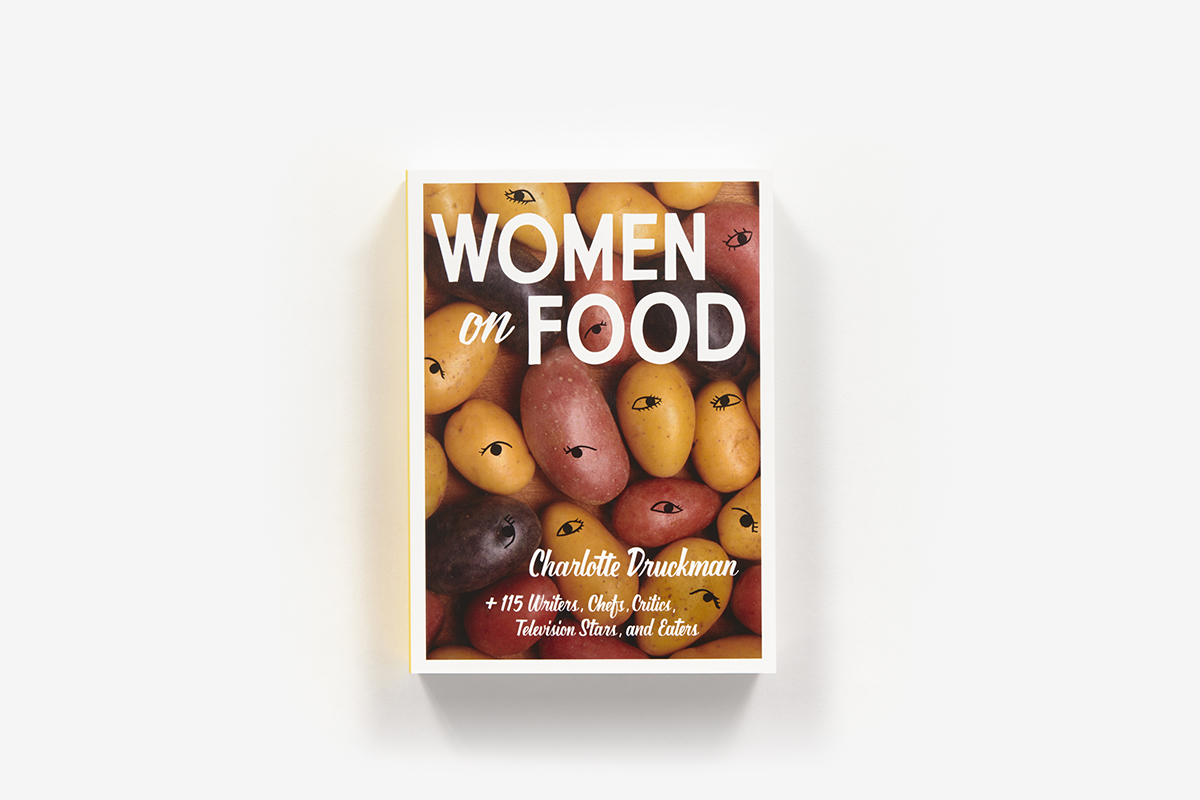

Druckman, Charlotte + 115 Writers, Chefs, Critics, Television Stars, and Eaters (2019) Women On Food. New York: Abrams Press. 400 pp. ISBN 978 1 4197 3635 3; eISBN 978-1-68335 681 3.

Ellen Messer (Tufts University)

The day before all the libraries closed down to reduce spread of COVID-19 infections, I happened upon this collection of Women on Food writings in my local Newton (MA) Free Library. This multi-colored, 400 heavy-weight-page volume assembles an extraordinary variety of women’s voices, which present themselves in multiple sizes and sexual orientations, livelihoods and lifestyles, and span multiple generations and racial/ethnic/ religious identities, priorities, and themes. As Druckman indicates in her introduction:

What you’re getting into is an anthology about women in—and on—food. That means women who work in or around food in some capacity, and what they think about that…and what they think about what you expect them to think about that.

Her interview questions encourage these women to “speak the truth…completely…[to] be analytical, furious, funny, serious, sad, harsh, silly, challenging, old-fashioned, avant-garde, creative, macho, pensive, unforgiving, unforgivable, opinionated, neutral must plain weird…[to] talk about what it’s like, really, to work in the food industry or food media, to get a meal on the table, or feed a community…[to] write about that without having to match the format or adhere to a particular genre or style” (p.6).

The anthology collects original stories, told mostly in prose although occasionally in poetry or in visual forms (drawings, photography, pictures of food, or food people or places). These single-authored pieces are mixed in or “up” with two-person “conversations” (Druckman interviewing respondents) and multiple short-responses to Druckman’s provocative queries on leading topics. Two early examples of this Q&A are: “LEXICON. Are there any words or phrases you really wish people would stop using to describe WOMEN CHEFS (or really, women, period)?” (p.8) and “COOK THIS, NOT THAT! What is a type of FOOD you wanted to cook and were told you couldn’t—or are made to feel as though you couldn’t…and you’re pretty sure it’s because you’re a women?” (p.67).

Cross-cutting themes across formats include female chefs’, but also food writers’ and editors’ experiences with sexual harassment and gender discrimination, personal and professional relationships (negative and positive) with ethnic foods, identities, and heritages, and their reflections on the significance of their mothers (occasionally grandmothers, less often fathers) on their food-focused career choices and signature dishes. Not one to steer clear of controversy, Druckman at the end of the volume also asks respondents to self-reflectively share their own personal experiences of complicity—“The C-word”—where they imagine how they, by acts of commission or omission, intentionally or incidentally contributed to women’s subjugation and harassment, particularly in the restaurant business, but also in media.

As in any collection of writings, readers will find some topics and narratives of greater interest than others. Reflecting my interests in food, religion, and human rights, I found “A Conversation with Devita Davison” (interview format) (pp.144-152) profoundly moving because her responses to Druckman’s leading questions touched on the essential roles of institutionalized religion and faith in advancing her Detroit-based food activism. In its most recent iteration, her activist problem-solving vision and skills for Detroit’s Food Lab, partnered with African American churches, whose underutilized kitchens facilitated and encouraged small-scale food-processing businesses by low-income women of color, helping them climb out of Detroit’s poverty and hunger while preserving traditional culinary knowledge and products, and contributing to the larger challenges of constructing healthy, sustainable, local food systems. Chief among Davison’s “pressing concerns” (Druckman’s final question to her) are the decline of Black churches and a growing awareness that “capitalism is going to destroy every single thing that these grassroots, community-based organizations were able to create.” Whereas an earlier era saw church women and kitchens as drivers of community programs, civil rights, and philanthropy, “the churches in our community are losing their power…[as] the demographics of the church are getting older” and younger people do not affiliate, participate, or maintain their significant presence and power in Detroit’s communities. Churches that used to fund social movements are in decline, and as a result, community organizers turn to foundations, but “foundations are not going to get us to freedom and liberation…I want to create an organization and then be able to share a model for other people to create an organization that’s funded by the people for the people.” (pp. 101-102). This interview, in particular, captures the strengths of the interviewees and the many ways Druckman’s questions and directions, in these and other formats, bring forth the depth and passions of their experiences and reflections.

My second favorite entry was Tienlon Ho’s essay, “The Months of Magical Eating” (pp. 80-92) which described her parent and grandparent generations’ traditional wisdom and medicinal arts as contributions to her “eating right” (birds’ nest soup, ginger) during the final months of her pregnancy and immediately following her successful childbirth. She ends by noting she still keeps a jar of this concentrated tonic in her refrigerator: “It is a jar filled with a family’s strength, a nascent wisdom, and the memories of ages that allowed me to bear the weight of this new life barely started.” (p.92). Her lyrical writing evoking visceral images and ideas substantively connect the individual female, through food, to cosmic forces and familial relationships beyond her present self or generation.

A third example that touched me particularly in these times of deep reflection on structural, racist violence in US society, was Von Diaz’ story, “Sitting Still.” Set in the South, it unveils the horrific legacy of lynchings through the telling lens of a simple recipe for “Bobbie Hart’s Banana Pudding” (pp.308-316).

As a collection of food writings by more than 100 female authors, the anthology includes interviews and essays with well-known food historians, cook-book authors, and essayists, including Betty Fussell, Jessica Harris, and Bee Wilson. Wilson’s sharply terse and topical piece on the advantages and disadvantages of evolving “Labor Saving” technology (pp.254-263) for getting essential food on the family table, accessibly touches on so many work-life dilemmas involving feeding and food preparation, offering practical advice without being preachy or pretentious. The words and images of Kristina Gill, “A Fig by Any Other Name” (pp. 375-383), illustrated with luscious and colorful sexual food imagery, is a clever and subtle triumph for all to enjoy. Some readers may savor the published volume’s bright color coding (strong to paler orangish to greenish yellows setting off two-person, multi-person interviews or Q&A, and essays). I found the varying hues bold, but also distracting, and wish the heavy paged book had weighed a bit less, to make it more physically comfortable to position and read. These hard-copy features may or may not translate discernibly into on-line, tinted copy, where volume weight is not an issue. As SAFN (and other) food-studies readers move in and out of quarantines, they might want to access and read the electronic version, and recommend various particular chapters to students and other colleagues and friends. In the meanwhile, now that my local library is allowing (scheduled, outdoor) book pick-up’s and returns, I hasten to review and return the hard copy for other potentially appreciative readers.